Alien Saga Blog

“Serve In Heaven Or Reign In Hell?”

ALIEN: EARTH | A POST-MORTEM REFLECTION

Wendy, Joe & Nibbs

It’s been nearly three weeks since the season finale of Alien: Earth released on FX, and as expected, fandom has been all over the place. At Perfect Organism: The Alien Saga Podcast, we were deep in the trenches covering the series from Noah Hawley, starting back in February. What followed was a whirlwind of interviews, aftershows, convention appearances, and sleepless nights. Now that the dust has settled, so have my thoughts.

Alien has always been a tough nut to crack. Since 1986, we’ve been chasing that elusive feeling, the mystery, the terror, the humanity that defined the first two films. When Episode 8 of Alien: Earth dropped, it became clear that, once again, we were facing a divided fandom and a product with both much to love and much to question.

In recent years, each new Alien entry, from Prometheus to Romulus to Earth, has arrived under a flood of director commentary and pre-release promises. Fede Álvarez warned of the dangers of “member berries,” while Noah Hawley vowed to re-mystify Giger’s perfect organism. Yet, when their projects finally reached us, what was said and what was delivered didn’t quite align. That dissonance erodes audience trust. Film and television landscape has dramatically changed. Gone are the days of intimate production diaries and year-long anticipation cycles. Marketing now typically begins three months before release, and the creative conversation often stops once the show premieres. Alien: Earth spent over five years in production limbo, from COVID shutdowns to the writers’ strike, obstacle after obstacle stood in the way. For a while, it seemed it might never happen. Then, suddenly, the strikes ended and filming restarted.

Kirsch is taken down during a fight with Morrow.

From the start, fans were cautious. The very title Alien: Earth carried weight, a callback to Alien 3’s original teaser, which famously promised “on Earth, everyone can hear you scream” before Fox pivoted, brought back Ripley, and delivered something far stranger. For many fans, that history remains a ghost haunting every new announcement. Like Ripley herself, the Alien fandom suffers from a kind of collective PTSD. We get excited, we hope, and too often we’re left disappointed. The question isn’t just whether studios can “get it right” anymore, it’s whether anyone truly understands what “right” even means for this franchise. Over the last several years, covering this series has become more than a creative pursuit. It’s become a study in human behavior. With every new installment, the same pattern repeats itself: anticipation gives way to anxiety, and anxiety gives way to outrage. The conversations we once had about art, ideas, and craft have turned into tribal declarations about who is “for” or “against” something.

When we as a podcast praised Alien: Earth, we were accused of being paid by FX. When we criticized it, we were accused of hating Alien or failing to “get it.” If we tried to hold space for both perspectives, we were told we were censoring the voices of those who disagreed. Division once again has reached a fever pitch where a difference in opinion feels like a crime. Lines are drawn in the sand. Longtime friends in the fandom stop speaking. Others are made to feel small or stupid for seeing something differently. Some of the comments hurled online carry such venom you’d think a sacred trust had been broken, not that a TV show had failed to meet expectations. The result is a fandom fraying from within. The more it happens, the more the community erodes. The line between critique and cruelty blurs until no one remembers what side they’re on. I’ve seen creators step away entirely, burned out by the very audience they once sought to entertain. I’ve seen thoughtful people withdraw from conversation because it no longer feels safe to love something publicly.

An injured Hicks waits on the drop ship for Ripley to return.

The irony, of course, is that Alien has always been about survival through unity, people of different backgrounds coming together to endure the impossible. But online, the opposite has happened. What should be shared love has turned into a competition for moral superiority. The fandom, in many ways, mirrors the chaos of the worlds it adores. It’s exhausting. And yet, we stay, because something about this universe still means something to us. The Alien IP might be the most difficult sandbox to write for. The first two films, Ridley Scott’s Alien and James Cameron’s Aliens, are triumphs of vision and script. They’re about tension, psychology, and detail. The writing makes or breaks it. And lately, the writing has felt unfinished, even when the world-building and performances shine.

Hawley’s scripts reportedly sat ready for years before cameras rolled, which makes it all the more curious that so many story threads felt undercooked or unexamined. Alien has always been in-part about precision, the small choices, the logic of the world. There’s a reason fans still debate Ripley’s adherence to protocol, or Ash’s violation of it. We care about cause and effect. Why didn’t a Weyland-Yutani representative chase the crew of the Corbellan as it ascended to the Renaissance space station in Alien: Romulus? Why does Alien: Earth’s Wendy succeed while the other hybrids fail? If Boy Kavalier can literally see through the eyes of his hybrids, how does he miss what’s right in front of him? The more you look, the more the fabric frays. That said, Alien: Earth isn’t without soul. Whether you loved it, hated it, or landed somewhere in the middle, the series offered something fresh: new characters with agency, a story uninterested in nostalgia-baiting. That alone deserves respect.

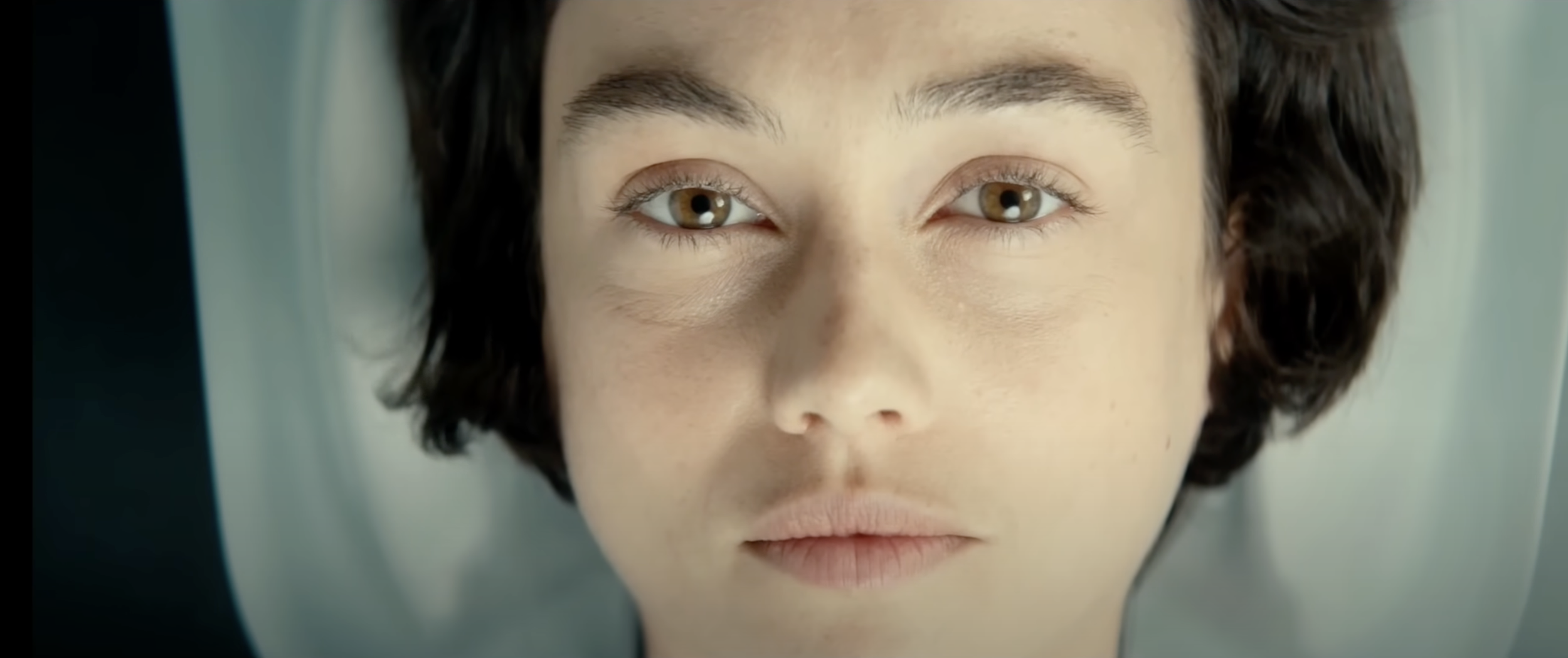

Sydney Chandler as Wendy.

Where Earth truly shines is in the questions it asks. What does it mean to be human? What is humanity, exactly? Is it something worth preserving? These are big, bold questions, closer in spirit to Blade Runner than to Alien. For some, that divergence was too great. For others, it was exactly the evolution the series needed. But by the finale, audience enthusiasm had cooled. Ratings dropped, conversations turned skeptical, and the season ended not with a bang, but a quiet thud. As of this writing, FX has yet to announce a renewal. For me, the show began to lose its footing in how it depicted the creature itself. That unraveling began in Episode 5, when the alien’s movements started to feel strange, stylized, almost dance-like. By Episode 7, Wendy, played brilliantly by Sydney Chandler, was petting the xenomorph in an open field, surrounded by onlookers who treated it less like a cosmic nightmare and more like a curious animal.

By the end, the creature had become something to command, even summon on cue. For all of Hawley’s strengths, his character work, his ideas, this particular choice undercut the series’ central terror. The alien isn’t a pet, or a symbol to be tamed. It’s unknowable, and that’s what makes it terrifying.

A Xenomorph attacks Joe Hermit.

The creature’s design, too, left many fans uneasy. Hawley explained that he’d leaned toward an “earth-like insect” aesthetic, hoping to make it feel grounded. But in doing so, he stripped it of its otherworldly essence. Giger’s design was never meant to be familiar. It was meant to be unreadable. By the final moments of Alien: Earth, the Xenomorph looked less like a nightmare from beyond and more like a man in a rubber suit, the worst fate imaginable for this creature. It had been robbed of all mystery, all agency, all power. If Alien: Earth returns, I hope what’s renewed isn’t just the story, but the reverence, for the creature, the myth, and the atmosphere that made this universe timeless. The Alien saga doesn’t need bigger worlds; it needs deeper ones. Fear, silence, and mystery built this franchise, and they can save it again. I also hope the fandom finds that same balance, to debate without hostility, to disagree without tearing down, and to remember that love for this universe is the one thing we all share.

Jaime Prater for Perfect Organism: The Alien Saga Podcast

Alien Romulus and Dehumanization

Alien Romulus and Dehumanisation

By Louis Gooding-Fair

Alien Romulus emphasises the theme of dehumanisation. It tells the story of a group of miners who attempt to leave their oppressive world behind, accessing an apparently deserted research station to acquire the supplies necessary to travel to a better world. Dehumanisation manifests in the followings ways:

Dehumanisation of employees

Dehumanisation via violence

Dehumanisation of technology

Dehumanisation of Andy (as an autistic coded character)

This essay will analyse each in turn, beginning with providing a definition of dehumanisation and the elements of it.

Definition of dehumanisation

Haslam defines dehumanisation as, “involving the denial to others of….characteristics that are “Uniquely Human” (“UH”) and those that constitute “Human Nature” (“HN”). Denying UH attributes to others reduces them to being animal-like, and denying HN attributes to others reduces them to objects or automata. Dehumanisation is viewed as a central component to intergroup violence because it is frequently the most important precursor to moral exclusion, the process by which stigmatized groups are placed outside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply.

Definition of “Stigma”

Dehumanisation may be preceded by the attachment of a stigma. A ”stigma” is the denial of attributes which make us human to an out-group, such as the capacity to feel and the capacity to make decisions. A stigma aims to reduce a person or a group “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one”. Goffman suggested that “the person with stigma is not quite human”; stigmatised groups are viewed as ‘less human’. Stigmatising an individual or group enables them to be dehumanised, even if that person is not human but displays human traits. This allows us to see others as non-human or less than human as their human characteristics have been removed or discounted.

Definition of “Uniquely Human”

Uniquely Human (“UH”) characteristics primarily reflect socialization and culture, are acquired rather than innate and are likely to vary between people and cultures. Markers of UH include language, higher order cognition, and refined emotion (“sentiments”), as well as pro-social values involving moral sensibility. UH include cognitive sophistication, culture, refinement, socialisation, and internalised moral sensibility.

Definition of “Human Nature”

In contrast, Human Nature (“HN”) is seen as the core properties that are fundamental and inherent to humanness. Haslam suggests that HN consists of three elements;

Characteristics which link humans to the natural world and their inborn biological dispositions;

Should be species typical, prevalent within populations and universal across cultures; and

Should be seen as deeply rooted, unchanging and inherent in nature.

The first and overarching form of dehumanisation is that experienced by Rain, Tyler, Bjorn, Kay, Navarro and Andy (“the Corbelan Crew”) as miners at the hands of Weyland-Yutani (“The Company”), which compels them to leave Jackson Star (“Jackson”) for Yvaga.

Dehumanisation of Weyland-Yutani employees

The Corbelan Crew are subject to organisational dehumanisation at the hands of The Company. It is this treatment and possibility of death through employment in dangerous positions which acts as the impetus for the Corbelan Crew to leave Jackson. This manifests in three ways:

Employment in degrading positions

Use of unfair employment conditions - Forced Labour vs Slavery

Use of a barrier to obscure or detach

This section will define the meaning of organisational dehumanisation and how it relates to the above.

Definition of organisational dehumanisation

Organisation dehumanisation is the process of an organisation treating employees like machines rather than humans, having less concern for their respects, and handling them as a means to achieve organizational objectives with less capacity for willingness and sentiments.

Application of organisational dehumanisation

The employment clerk represents the organisational dehumanisation by The Company. She uses Rain to achieve organisational objectives by reassigning her to the mines despite Rain meeting her contracted hours and without her consent, “Due to a shortage of workers”, which is where Rain’s parents died. She operates with less capacity for willingness and sentiments, displaying no empathy when Rain discloses that her parents had died recently and as a result of working in the mines, and is derisive of Rains plan to leave Jackson. After her forced reassignment, she offers an insincere platitude devoid of feeling, “Thank you, and remember the company is really grateful for your ongoing service.” This behaviour highlights that she does not display elements of UH or NH; her position may suggest that she is subject to the same oppression as she is administering, may be synthetic and may have consigned others to their death in the mines previously. It is worth noting that where Weyland-Yutani is typically represented by men in positions of power (Ash, Carter Burke, Michael Bishop Weyland and in Romulus, Rook), Romulus uses a female employment clerk, a lowly administrative position.

Organisational dehumanisation is displayed via the use of primitive working practices; a worker is shown carrying a canary to a mine, which reflects cost cutting measures used by The Company and little they value the lives of their workers. It underlines that humans are seen as disposable and replaceable. In contrast, synthetics occupy positions of power, with one sacrificing miners lives to save many. Synthetics are superior to humans as they act as agents of the Company, having being programmed with company goals and objectives, as well as being granted access to company systems.

1. Employment in degrading positions

The Corbelan Crew seek to escape the organisational dehumanisation they experience as miners which resulted in the deaths of their parents. Rain, Tyler, Andy, and Kay are employed as miners, with Navarro employed as a pilot, and are subject to the stigma of working in a dirty and dangerous profession, as their parents were. Mining is a dangerous occupation which can cause long term health issues and death. Occupations which are dirty or dangerous may have a negative stigma attached to them, and are known as “dirty work”. This is work which has either a physical, social or moral taint attached. These are defined as:

Physical taint - when an occupation is thought to be performed under particularly dangerous conditions or is directly associated with dirt, garbage, and effluent.

Social taint - a worker occupies low-status and low-power positions and has a subordinate relationship with others (e.g., butlers or waiters).

Moral taint - a worker employs methods that are deceptive or immoral.

Mining is a physically tainted profession as miners are visibly dirty, and it is a dangerous profession; Rain states her parents died from lung disease as a result of employment in the mines. Rain was employed as a farmer, although the type of farming is not stated. Raising livestock would involve feeding and cleaning up after animals; killing livestock would involve processing carcasses. If farming vegetables, this would likely take place in greenhouses and with unnatural light as there is no sunlight on Jackson. This may also be considered dirty work as Farmers work with soil. Given the small size of the colony it is likely that Rain would have been responsible for livestock and vegetables. Andy is also physically tainted as he was originally a mining synthetic, which could damage him (and may be the reason why he was discarded).

As a mining synthetic, Andy is socially tainted. Employed as a mining synthetic, he is slave labour, occupying the lowest status and power positions in the corporate employment structure. As Rook states, “Your model was once the backbone of our colonisation efforts”. As a synthetic he requires no salary or allowance to live on and was considered expendable by the company. He becomes subordinate to Rook upon being upgraded, “What’s required of me…Sir?”, having been summoned by Rook.

While not dehumanised through treatment, Rooks research into the Prometheus pathogen is morally tainted as it is intended to be used on the Jackson miners, presumably against their will, which will mutate its host, with the aim of exploiting them both after death and before death (as a pre-emptive measure). This is unethical behaviour. Andy is also morally tainted after receiving the upgrade as he is facilitating the transport of pathogen to Jackson to enable it to be administered to the miners.

The humans are physically tainted because they are forced to; Andy is socially tainted as he is designed to; and Rook (and Andy) are morally tainted in complying with creating and facilitating the Z-01 pathogen which will harm its intended hosts - humans.

2. Use of unfair employment conditions - Forced Labour vs Slavery

Jackson is dirty, oppressive and dangerous and that while we do not know the background to how the characters got there, it is suggested that the employment arrangement is tantamount to either forced labour or slavery.

Forced Labour

Forced labour is defined as, “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily." It is considered a form of modern slavery and occurs in manual industries. In the modern day, forced labour is statutorily prohibited. Forced labour consists of three elements.

Work or service, which refers to all types of work occurring in any activity, industry or sector including in the informal economy.

Menace of a penalty, which are used to compel someone to work.

Involuntariness, the terms “offered voluntarily” refer to the free and informed consent of a worker to take a job and his or her freedom to leave at any time.

The Corbelan Crew may be subject of a forced labour arrangement. The work/service aspect is met as Rain is employed for the Company in the farming division, and later reassigned to the mining division. The menace of penalty is implied by Tyler stating, “...this company, they’re not gonna give us anything”, which suggests The involuntariness element is met as Rain does not consent to the increase in her quota or her work location, which appears to be non-negotiable, “Unfortunately, quotas have been raised to 24,000 hours, so you’ll be released from contract in another five to six years.” This is reinforced by the Jackson revolutionary stating, “We’re all the company slaves.”

Slavery

Slavery is defined by the UK’s Modern Slavery Act [2015] as being circumstances whereby;

the person holds another person in slavery or servitude and the circumstances are such that the person knows or ought to know that the other person is held in slavery or servitude, or

the person requires another person to perform forced or compulsory labour and the circumstances are such that the person knows or ought to know that the other person is being required to perform forced or compulsory labour.

Additional considerations are given to the circumstances of the individual relating to such as the person being a child, the person's family relationships, and any mental or physical illness which may make the person more vulnerable than other persons;

Forced labour is an element of slavery, and the conditions of this are met. This means that the terms, rights and negotiation power is weighted in favour of The Company. The revolutionary conforms they are slaves; stating, “They sell us hope to keep us slaves.” Furthermore, the employment clerk is made aware that as a result of her parents dieing that Rain is vulnerable, but increases her quota regardless.

While it could be suggested that The Company may increase the quota as a result of a contractual clause, “you’re not eligible for contract release yet” legislation prohibiting slavery or forced labour would override any clauses within the employment contract which are tantamount to slavery, as is the case with the Modern Slavery Act 2015.

In contrast synthetics are shown in positions of power. Rook is employed as a senior scientist to extract and refine the pathogen from the black goo, for its intended use on humans. Synthetics are responsible for mining operations which may involve making difficult decisions, such as sacrificing some to save others. “so a synthetic made the call to seal them, with Bjorn’s mom still trapped inside.” Despite being a mining synthetic, Andy is in a position of power through his ability to access company systems, something the human are unable to do, “He speaks Mother. He can access a terminal on the ship.” After the update Andy becomes responsible for completing Rook’s mission and essentially represents the company. Synthetics are superior to humans as they act as agents of the company, programmed with company goals and granted access to company systems. They come with higher manufacturing costs; whereas humans are cheap, replaceable and disposable.

The dehumanisation of synthetics depends on their position; where Bjorn dehumanises Andy (a reclaimed mining synthetic), he does not dehumanise Rook (a Weyland-Yutani scientist). He attributes Rook a gender, “So what the fuck is he sayin’?”, in contrast to Andy where despite using male pronouns, states, “It’s just Wey-Yu damaged goods.” The interaction between Bjorn and Rook took place after Navarro had been subdued by the facehugger; he may not have attempted to dehumanise Rook as Rook demonstrated knowledge of the facehuggers capabilities and the implication of the attack on her. Another reason may be that the synthetic who killed Bjorns mother and Andy may have been of the same model or class of mining synthetic whereas Rook was a science synthetic who appeared and acted differently. Rook and Andy possess different dispositions; Andy is “child-like” whereas Rook is assertive, authoritative and knowledgable of the research undertaken on the station. Given that their employment on Jackson is akin to forced labour, Bjorn may have perceived Rook as an authority figure and learned that challenging authority was futile.

3. Use of a barrier to obscure or detach

Company employees are dehumanised by the use of a screen to obscure or to act as a barrier to create detachment or distance. The use of screens appears consensual. The use of the barriers and screens creates distance and detachment which enables organisational detachment to take place. The first example of this is the suits used by the Renaissance scientists. They strip them of their identity by preventing us from seeing their faces and have no name tag on them. This preventing us from determining their name, gender, or status as a human or synthetic. The scientists we meet later on have been mutilated; Rook is missing the lower half of his body and the only human scientist we meet is found hanging dead, missing his brain and the back of his skull.

The employment clerk sits behind a clear barrier. This has an effect of creating a distance and detachment from Rain. Rook similarly appears later on monitors which creates distance. This creates a distance between then and audience, enabling the employment clerk and Rook to consign Rain to death while delivering detached and insincere platitudes.

Summary

The Corbelan Crew are subject to organisational dehumanisation, via their employment in dirty and degrading positions, in an employment arrangement akin to forced labour or slavery, while the Company uses barriers and screens to create a sense of detachment in administrative staff, which enable organisational dehumanisation to take place.

Dehumanisation through Violence

Dehumanisation can manifest physically through acts of violence. The aggressor sees the victim as not possessing the same characteristics that they possess, perceiving them as “less” and “not human”. As such it makes it easier to inflict violence on them. The film (and one of the research modules) is named after Romulus, from the myth of Romulus and Remus. This myth is inherently violent and contains elements of dehumanisation via rape and murder, and reflects the research taking place on the Renaissance. While dehumanisation takes place through internal and external acts of violence, the contexts and methods of internal violence are expanded.

Inherent Violence

The Roman myth of Romulus and Remus involves violence, rape, and dehumanisation of children. According to the myth, Romulus and Remus were conceived by the vestal virgin Rhea Silvia, who was forcibly impregnated by Mars, the Roman god of War. Her uncle Amulius then ordered a servant to kill the children, but this servant showed mercy and let them drift down the river where a wolf tended to them. Rhea herself was later spared death. Later on, Romulus killed his brother which lead to the founding of Rome. This myth highlights the internal violence of rape and external violence of murder, which occur in the film.

Given the criticisms of the characters for looking like “children” this is perhaps fitting, as it alludes to the abuse of children who been abandoned by their parents (as they have died). Similarly, they were conceived and born into violent times, and have been dehumanised by people more powerful than them. This myth alludes to the nature of the research onboard the Renaissance, which is aimed at developing methods of removing the autonomy of the individual, most notably the Z-01 pathogen but also the facehuggers which the Plagiarus Praepotens was extracted to create the pathogen.

1. Internal violence

Internal violence may be defined against the autonomy of the individual. This takes three notable forms; the upgrade which forcibly overwrites Andy’s personality, Kay using the Z-01 on her foetus and Navarro’s death after being attacked by a facehugger. Notably, through Bjorn attacking the Xenomorph while it is gestating may be the first example where a human has engaged in a rape-like act on a xenomorph.

1a) Andy and the module upgrade

Regarding Andy, the WY module forcibly reprograms Andy, overwriting his personality, autonomy and self identity. Afterwards, he identifies not as “Andy” but as a model; one of many, “...an ND-255 Weyland-Yutani synthetic, originally built for mining and safety tasks.” Rook also identifies him using his model number. While the Andy name is an acronym of his model designation, the name makes him feel “human”, gives him personality and distinguishes him from other synthetics. Referring to him by his model number strips of his human attributes and reduces his purpose; having been programmed by Rains father with a personality and the goal of doing, “...whats best for Rain”, and recognised as a family member, he is a tool, and one of many of the same type. The module has its benefits; as Andy states, “It substantially updated my AI, and it’s mending my motor systems as we speak.” This update arguably benefits Rain and Tyler too; he is able to stop a lift descending one handed and judge closing doors to a more accurate degree. It does not update his knowledge base, ensuring he is subservient and unable to assist Navarro or provide insight into the research on Renaissance.

1b) Kay’s foetus

Kay injects herself with the unstable Z-01 mutagen, in order to heal from her injuries. Kay did not intend to hurt herself or her unborn child. Rook states its effects, “Its symbiotic capableness easily rewrites the host’s DNA through its blood.”, and Kay is not made aware of its effects on test subjects. Rooks comments are correct; Kay’s foetus is born unnaturally in an acidic cocoon, where its features and characteristics resemble those of the engineers or a xenomorph. It develops incredibly fast without taking on any biomass, and is violent and aggressive. Rook’s work was to overwrite the autonomy of the individual at a cellular level.

1c) Attack on Navarro’s

Male rape is a central theme to the Alien saga, Navarro’s attack by a facehugger is consistent with that. While the victim is typically a human male (Kane is Alien, Russ Jorden in Aliens and Oram in Alien Covenant, as well as Milburn being attacked by a Hammerpede), Navarro is female, but displays an androgynous appearance by being shaven headed. In contrast, the face huggers are unable to successfully subdue Bjorn or Tyler and Andy is not considered a host. The facehugger attacks Navarro, violating her autonomy and is reduced to being a host, dieing upon the birth of the chestburster.

2. Bjorn and the Cocoon

While internal violence is carried out against members of the Corbelan Crew, Bjorn inverts this by attacking the xenomorph with a cattle prod whilst it is gestating. The depiction of this stage of xenomorph development is unprecedented, and this type of attack has not been seen previously. This scene may be construed as a rape scene, as the prod is phallus shaped and the cocoon resembles a vagina. In this case, the prod is melted by the acid produced by the cocoon which nullifies the attack, followed by Bjorn being struck by a tail – another phallic object. Bjorn’s fingers (also phallic shaped and which may be used in sexual acts), have been burned to the bone by the acid produced. It is worth noting that both Rain and Tyler describe Bjorn as a “dick” at other points in the film. We find out that Kay was impregnated by someone unknown, which may allude to “immaculate conception” of Romulus and Remus. We later find out that Bjorn is the father, who displays aggressive tendencies (towards Andy), perhaps akin to Mars, the Roman god of war.

External violence

External violence is defined as violence against the person. Andy is the victim of physical threats and acts of violence from different characters. The first instance of violence against Andy is the attack by a group of children outside the employment office. The prelude to this attack one of the children pointing a weapon at him, which he did not perceive as a threat. The reason for the attack is not given, (suggested reasoning might be that he was attacked because he is synthetic, Company property or displayed characteristics which showed he was “different”) although it is suggested he did not fight back, or was overwhelmed. It is likely that he was attacked as he was company property, given that synthetics operate in a position of authority and that he was a recognised mining synthetic.

The second instance is the threats and acts of violence from Bjorn towards Andy. Andy is stigmatised by Bjorn for the actions of another mining synthetic, who sacrificed Bjorn’s mother to save a number of other miners. Bjorn never identifies Andy’s model as the synthetic which authorised this course of action; it is unlikely he is targeting Andy directly. Regardless he repeatedly threatens Andy, “I could probably fry a synthetic with one of these…” This is attributed as aggressive banter, however when Andy prevents Bjorn from falling down a hole, he perceives this as retaliation; and attempts to pass them off as a joke. He later attacks an updated Andy with a cattle prod when he states what Navarro’s chances of survival after being attacked by a facehugger, calling him a “bitch”.

The third and final instance is by the Offspring, which upon maturing and finding Andy standing in front of Kay, slashes him across the neck, causing him to bleed and struggle to function.

Summary

In summary, the Romulus myth contains acts of violence of dehumanisation, which alludes to the nature of the Renaissance’s research and the scope of internal acts of dehumanisation are expanded beyond male rape.

Dehumanisation and technology

Dehumanisation and technology interact in two ways; dehumanisation of technology (Andy as a synthetic) and dehumanisation via technology (Z-01 research, facehuggers and module upgrade).

1. Dehumanisation of Andy (as a synthetic)

Romulus considers whether a synthetic (Andy) can feel pain and emotion and if so, whether he can be attributed moral status. Andy is dehumanised because the human characters believe that he is unable to experience or demonstrate emotion and pain. This belief influences his treatment by different characters.

Andy is subjected to mechanistic dehumanisation, which is where an in-group is characterised as having NH qualities fundamental to being and the out-group is characterised as being mechanistic and unable to experience emotions or suffer pain, which precludes them from being attributed moral status. It is closely tied to emotions; mechanistic dehumanisation involves seeing others as inert, cold, passive, rigid, superficial, or as a collection of parts. Mechanistic dehumanisation is more likely to occur in interpersonal interactions and organizational settings, which is demonstrated by Bjorn’s interactions with Andy. Research has found that a robot must be humanised in order to dehumanise it. Bjorn attributes Andy a gender, before dehumanising him. “He’s not your brother. It’s just Wey-Yu damaged goods.”

It is suggested that the experience of pain implies sentience and consciousness, which involves body and mind, and a central nervous system which receives and transmits pain signals. As such robots or synthetics do not feel pain like humans do, however this does not stop Rain from believing that he can feel pain.

Research has shown that people are more likely to attribute moral status to a robot when they believe it is capable of experiencing emotions. Andy demonstrates that he is capable of displaying emotion; when Rain asks how he could leave Kay to be taken by the xenomorph, he responds by asking, “What? Leave someone behind?” This implies Andy felt rejection as a result of Rains decision to go to Yvaga without him. Bjorn’s threats and aggressive behaviour is based on the idea that Andy feels fear, which is supported by Andy’s submissive behaviour when Bjorn is confrontational. After threatening Andy with a cattle prod and justifying it on the basis of, “Just in case you have any fucking funny ideas”, Andy grabs Bjorn to prevent him falling down a hole, which he perceives as aggression stating, “It’s a joke. I was joking.” Andy also displays selflessness and appears to stifle an external display of disappointment stating, “If it’s what’s best for Rain, it’s what’s best for me.” Despite Andy demonstrating emotion he is not attributed moral status by the Corbelan Crew, and while Rain feels guilty she did not alter her plans to take Andy with her.

Where research participants have been confronted with the victimisation of a robot, participants might find themselves conflicted between an automatic visceral reaction (the harm-made mind effect) and a post-hoc rationalization process (the justification of harm via dehumanisation). Rain displays the former; she instinctively protects Andy or goes to Andy’ aid. This is exemplified when she stops the children attacking him outside the employment office. Navarro perhaps embodied the latter; she unsuccessfully tries to ease Rain’s guilt by stating that “He’s not…you know, real”. The reason for this reaction is that Rain sees Andy as family and as her only family remaining she has a duty to protect him as he does to protect her. As such, whether he actually feels pain or not is irrelevant, since she perceives that he can. We sympathise with Andy despite him being an “artificial person.”

In contrast, research has found that the willingness of individuals to violate moral principles during human-robot interaction is grounded in the belief that robots cannot suffer. Before the upgrade, Andy is treated as lacking UH characteristics and as such is child-like and vulnerable. Bjorn’s treatment of Andy is predicated on the idea that he can feel pain, while seeing him as an object. Bjorn considers Andy an object, “It’s just Wey-Yu damaged goods that your dad found in the trash” and a “fake person”, while stating “You fuckin’ bitch!” when Andy advises that Navarro is a danger to the crew. This highlights that dehumanise a robot or synthetic it must be humanised first, as well as Bjorns inconsistent view on synthetics. The inability to feel pain is often used as an argument why robots are unworthy of moral consideration; Navarro believes he cannot suffer stating, “He doesn’t care. It doesn’t matter to him. Okay? He’s not…you know, real.” However it is shown that whether he can feel pain or not is irrelevant since it is the perception of the individual and their willingness to extend human concepts onto a synthetic. It is this which enables Rain and Andy to survive.

The upgrade removes Andy’s HN traits and he becomes literally machine-like, embodying the mechanised dehumanisation that he has been subject to. The removal of HN traits enables him to make difficult choices and think tactically and unclouded by emotion; he does not save Kay from the xenomorph when he recognised that it was using her as bait, and armed Tyler and Rain with pulse rifles to use a distraction. He is detached; when Rain exclaims that Andy nearly closed the doors on Tyler he states, “Yes, but I didn’t. I calculated the timing perfectly with more success than last time. Won’t you agree?” This ability to assess the situation and surrounding contributes towards Rain and Andy’s survival, as well as enabling Kay to make it back to the Corbelan.

Whether Andy feels pain is down to whether the characters consider him able to feel pain regardless of how that happens; Rain comes to realise that he does and is somebody worth protecting, whereas Bjorn sees Andy an object, and Tyler, Kay and Navarro see him as a means to an end.

2. Dehumanisation via technology

Dehumanisation takes place through the Z-01 pathogen, facehuggers and the module, with pathogen and module referred to by Rook as an “upgrade”.

2a) Z-01 research

Dehumanisation via technology takes place via the use of the Z-01 pathogen developed by Rook. Much like the module for Andy, the Z-01 pathogen is aimed to improve humanity as Rook states, ““This is a much needed and well overdue upgrade for humanity.” The Z-01 pathogen was developed by Rook, who believed that humanity is unsuited for space colonisation, “Mankind was never truly suited for space colonization…. too fragile... too weak.” Rook states how the pathogen dehumanises its host; “Its symbiotic capableness easily rewrites the host’s DNA through its blood”. The crushed rat which had the pathogen applied came back to life but was horribly deformed. Kay applies the pathogen to herself which results in a mutated foetus born inside a cocoon, with engineer and xenomorph like features, and making it hostile and violent. The pathogen was intended be taken back to Jackson, presumably to be applied to the miners for the purpose of further exploiting them after death. What Rook shares with David is the perception of humanity as weak; where David sought to destroy humanity, Rook sought to improve humanity through a flawed and ultimately destructive means. Rook, like David, is impotent; he can only create something that is not derived from him and mutate what exists, he cannot procreate. The pathogen is the closest thing to breeding as he would get and is why it is means everything to him.

2b) Facehuggers

Rook uses the available technology to create a vast number of facehuggers from which to extract the Plagiarus Praepotens, and it is a facehugger which attacks the crew and subdues Navarro. As facehuggers are typically contained within ovomorphs, they have been developed unnaturally outside of their typical developmental cycle, this makes them different and they exhibit different qualities to typical facehuggers. Given the number of xenomorphs on the station, it appears that the Renaissance research staff have been subjected to attacks.

2c) The module

As stated, the module overwrites Andy’s personality, autonomy and self identity. It strips UH or NH characteristics that he possess and reduces him to being a slave to The Company. Rook can communicate internally with Andy and dictate what his objectives are “I heard your voice in my head. Calling.” This may place Rook as an inverted form of Rains father. Where he programmed Andy to have Rains best interests at heart and was human who has died, Rook is a Weyland-Yutani synthetic who has is alive and forces Andy to place The Company’s objectives first. Andy’s autonomy has been removed and is a subordinate of Rook, which returns him to his original programming as slave labour and is subjected to organisational dehumanisation. The module updates and repairs Andy’s physical capabilities, perhaps similarly to how the pathogen aimed to upgrade humanity, although these have been updated to enable him transport the pathogen off of the Renaissance. It also provides him with access clearance but does not provide him with information on the research, which keeps him subordinate to Rook. Rain sacrifices this “better” form of Andy for his original programming after she has seen what it has done to him, although without the upgrade it is unlikely she would have survived.

Summary

In summary, the technology developed and utilised on the Renaissance ultimately aimed to dehumanise its host by removing the hosts human qualities or taking away their autonomy.

Dehumanisation of Andy (as an autistic)

It has been suggested that Andy is an autistically coded character as the model number “ND-255 artificial person.” suggests. ND stands for neurodivergent; what this means in-universe is not stated. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has been defined as, “...a lifelong developmental disability which affects how people communicate and interact with the world.” While autistics display different charactersitics on the spectrum in different aspects, the extreme “poles” of behaviour may include child-like qualities and machine-like qualities, both of which are displayed by Andy.

Denial of personhood – removal of UH and NH qualities

Autistics have been dehumanised by society, academics and autism specialists by using language and actions to deny them personhood, as they believe they lack fundamental human qualities. Falcon and Shoop state, “It’s as if they [persons with autism] do not understand or are missing a core aspect of what it is to be human”; while Baron-Cohen stated, “Autistics lack one of the quintessential abilities that makes us human” Bjorn echoes these views, “He’s not your brother. It’s just the Company damaged goods that your dad found in the trash. And that’s all he is…”

Ivar Lovaass states, “One way to look at the job of helping an autistic kid is to see it as a matter of constructing a person. You have the raw materials, but you have to build the person.” These views suggest that NH qualities are absent from autistics the HN qualities fundamental to personhood, dehumanisation to take place. This is perhaps how Rains father saw Andy, who received programming to look after Rain, “I have just one directive. To do what’s best for Rain. Your dad wrote it.” The programming also provided him with UH qualities to enable Rain to recognise him as family, yet she intends to travel to Yvaga knowing that it does not accept synthetics.

Denying someone UH traits implies they are ‘child-like’ or lacking in self-restraint, and the denial of HN traits implies that they are ‘machine-like’ or lacking in emotionality or warmth. Andy displays the former before the update, and displays the latter after the update.

It may be suggested that before the upgrade Andy lacks UH qualities. He is obviously vulnerable, yet is dehumanised and manipulated by human and synthetic characters. Andy is aware that others see him as childlike; “Today, I can finally help. And you won’t see me as a child anymore.” His lack of impulse control is demonstrated by getting distracted by a fixed ball and cup game. He is non-violent and is physically overpowered by a number of children easily and does not retaliate towards Bjorn when he threatens or attacks him. The module upgrade overwrites his personality and goals, and enables Rook to manipulate him into attempting to deliver the Z-01 pathogen to Jackson.

The update removes Andy’s existing NH programming which makes him becomes ‘machine-like’, prioritising the delivery of the pathogen to Jackson. His speech becomes formal, using Received Pronunciation (RP), as used by Ash and David, and his focus is on the recovery and transport of the Z-01 pathogen. It strips him of his character and identity; he identifies as a model and does not recognise his name. “I’m an ND-255 Weyland-Yutani synthetic. Originally built for mining and safety tasks. You guys call me Andy?” Rook denies Andy’s personhood by referring to him by his model number, not his name; “ND-255 artificial person”. Your model was once the backbone of our colonization efforts.” Referring to him in this way strips him of his individuality.

In contrast, Rook is a name, not a model number and Andy does not correct Rook. Andy is subservient; he is a black mining synthetic who refers to Rook as “Sir”. Andy states, “I heard your voice in my head. Calling.” which implies that Rook possesses some form of control over Andy and reinforces Andy’s subservience.

The removal of the NH qualities enable Andy to think tactically and rationally; when Kay is being used to bait Tyler and Rain to open the door, Andy refuses stating afterwards, “We’d all be dead if I had.” echoing the choice of the synthetic who sacrificed Bjorn’s mother to save a greater number of miners, which was ultimately the correct choice. When attempting to pass through a corridor with facehuggers lurking, Andy advises Rain and Tyler to control their body temperatures to avoid detection by facehuggers; he is asking them to become “mechanistic”. They narrowly escape when Tyler becomes emotional at hearing Kay. Andy arms Tyler and Rain as a preventative measure, “...the creature may see it as a threat”. This decision enables Rain to defend herself against a head on xenomorph attack.

The Corbelan Crew and the Company attempt to exploit Andy to achieve their aims and objectives. Andy’s is considered useful by the Corbelan Crew for his ability to access the Company systems only, “He speaks Mother.” Andy is viewed as disposable by Rain as she intends to go to Yvaga without him, knowing synthetics are not permitted. Rook attempts to exploit Andy so that he can transport his pathogen to Jackson. After Navarro has been attacked and faces certain death, Rook advises Andy that humans can become emotional and irrational (“Humans go through too many emotional stages”), however when Andy chooses not to take the pathogen to Jackson, Rook succumbs to petty anger, “Now you better listen to me here, now, you two. You are insignificant in the great scheme of things.” They all fundamentally underestimate Andy’s position; as a synthetic the xenomorph does not perceive him as a target and is able to devise strategies to enable the Corbelan Crew to escape from the station. He the only autonomous synthetic and without him Rook is unable to transfer the pathogen to the colony.

Double empathy

“Double empathy” is defined as non-autistic people lacking insight into lives of autistic people, just as autistic people struggle with social insight into the lives of non-autistic people. When Bjorn tells Andy that Rain intends to leave him behind, he is expected to understand and accept it; however when Kay is used as bait by the xenomorph to open the door, which Andy does not do, Rain tries to appeal to Andy’s emotional side by asking how he could leave Kay behind, asking in response, “What? Leave someone behind?” His choice is the correct, and highlights that Rain and Tyler expect Andy to treat the humans with respect without showing the same back. This is also highlighted by Bjorn lashing out at Andy with the cattle prod when he advises her that Navarro should not go on the ship, while showing disregard to Andy’s feelings when he discloses that Rain will not take him to Yvaga.

Summary

In summary, Andy is an autistically coded character. He displays autistic traits, and is dehumanised by the denial of personhood by the Corbelan Crew and The Company who dehumanise and attempt to exploit him. They all underestimate him and his position within the story, and comes to be seen as someone worthy of respect.

Conclusion

Alien Romulus explores dehumanisation and its various iterations. The characters are subject to organisational dehumanisation by Weyland-Yutani as their employer, internal and external violence, of which involves technology, and the autistic coded Andy highlights the dehumanisation of a vulnerable individual.

Bibliography

Journals

Ashforth, Blake E; Kreiner, Glen E. Academy of Management. The Academy of Management Review; Briarcliff Manor Vol. 24, Iss. 3, (Jul 1999): 413-434.

Brown TR. The Role of Dehumanization in Our Response to People With Substance Use Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020 May 15;11:372. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00372. PMID: 32499724; PMCID: PMC7242743.

Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Understanding, attitudes and dehumanisation towards autistic people. Autism. 2019 Aug;23(6):1373-1383. doi: 10.1177/1362361318811290. Epub 2018 Nov 21. PMID: 30463431.

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An Integrative Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4 (Original work published 2006)

Haslam, N., Bastian, B., & Bissett, M. (2004). Essentialist Beliefs About Personality and Their Implications. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(12), 1661–1673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271182

Rothbart, M., & Taylor, M. (1992). Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In G. R. Semin & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language, interaction and social cognition (pp. 11–36). Sage Publications, Inc.

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Rubbab UE, Khattak SA, Shahab H and Akhter N (2022) Impact of Organizational Dehumanization on Employee Knowledge Hiding. Front. Psychol. 13:803905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.803905

Falcon, M. and Shoop, S. A. ‘Stars ‘CAN-do’ about defeating autism’, USA Today (updated 10 April 2002) https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/spotlight/2002/04/10-autism.htm, accessed 9 August 2018.

Chance, Paul (1974), ‘A conversation with Ivar Lovaas about self-mutilating children and how their parents make it worse’, Psychology Today, (January 1974), 76-84

Books

Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hughes E (1951) Studying the Nurse’s work. The American Journal of Nursing 51(5): 294- 295.

Hughes E (1958) Men and their work. The Free Press of Glencoe

Online Articles

https://www.ilo.org/topics/forced-labour-modern-slavery-and-trafficking-persons/what-forced-labour

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism

https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/movies/alien-romulus-2024-transcript/

https://neuroclastic.com/the-rampant-dehumanization-of-autistic-people/

https://theautisticadvocate.com/regarding-the-use-of-dehumanising-rhetoric/

Legislation

Modern Slavery Act [2015]

Podcasts

Fede Alvarez & Cailee Speany Cinemateaser Interviews (English Translation)

Huge thanks to our friend Thibaut Claudel, Writer & Narrative Designer of Aliens: Dark Descent, for his help translating this French interview into English. This article originally appears in French in Cinemateaser’s summer 2024 issue.

FEDE ALVAREZ interview

Since the prequels didn't satisfy many people, ALIEN tries to get back to what it does best: the horror of a closed-door space movie set in corridors contaminated by a large, deadly bug. At the helm is Fede Alvarez, whose since EVIL DEAD has proven that he excels in gory spectacles that test the viewer's resistance. After seeing an (impressive) part of his ROMULUS, we tried to find out what it was like for him to direct an ALIEN.

BY AURÉLIEN ALLIN

ALIEN: ROMULUS is the story of a double return to roots. Firstly, for the franchise which, after the fourth ALIEN: RESURRECTION directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet Jeunet in 1997, had been buried in opuses unworthy of its stature (the two ALIEN VS PREDATOR), followed by prequels too cerebral, too messy and too clumsy to fully convince (PROMETHEUS and COVENANT). Then for director Fede Alvarez who, after the great artistic and commercial successes of EVIL DEAD and DON'T BREATHE, had gone astray in THE GIRL IN THE SPIDER’S WEB, a flimsy techno-thriller - despite the visual talent he brought to it. A resounding failure that kept him away from the silver screen for six years and, he admits, also wore down his desire to make films. This Uruguayan, invited to Hollywood by Sam Raimi after an outstanding short film, ATAQUE DE PÁNICO, now dreamed of nothing more than directing an ALIEN. A dream he fulfilled after selling this idea to Ridley Scott: to place ROMULUS between ALIEN and ALIENS, to return to that futuristic yet primitive, industrial and rugged world, made up of miners and rough-hewn soldiers in space, suddenly confronted by creatures whose refinement is entirely devoted to death. And so it is that ALIEN, after almost three decades of wandering in search of a new identity, is reborn embracing the one he was born with. ALIEN: ROMULUS follows a crew of underage colonists dock at a Weyland-Yutani laboratory station, where they discover... We won't bore you with the details. An opportunity for Fede Alvarez to rediscover the violently dry and/or furiously gory spirit of his first two films, and to rekindle rekindle the sacred fire within him. In June, he came to Paris to present some fifteen minutes of ROMULUS, with Face Huggers stalking in packs like spiders on speed,

cocoons like murderous vaginas, and chest-busting seen through X-rays. ALIEN: ROMULUS seems to vibrate generously with the very primal pleasure of enjoying dolorism and dread. No doubt because Alvarez, while he won't be selling anyone the untenable 'CGI-free film' promotional spiel, has nonetheless done his utmost to keep ROMULUS organic, using a maximum of practical effects, animatronic creatures animatronic creatures and vast, solidly-built sets. Will this finally restore the shine to a saga which, in the past, shone by revealing or imposing future greats? We hope so. While we wait for the final verdict, we spoke to Fede Alvarez about his link to pre-existing class struggle, phallic symbols and mise en scène.

Aurélien: Three of your films are set in pre-existing universes. How do you explain this?

Fede Alvarez: Maybe I should think more strategically about my choices! (Laughs.) But the only thing I can do is jump in when I have a strong feeling that there's a project I really want to realize. EVIL DEAD was my first film. At the time, it was the first thing I heard about

that I found exciting. Really exciting. So I did it. After that, we made DON'T BREATHE - and then DON'T BREATHE 2, which I didn't direct, but co-wrote and co-produced. I remember, just after DON'T BREATHE, I didn't want to... (He pauses). I'd just made two big hits, which had more than they cost and, as you know, I'm from Uruguay. My upbringing revolved around the idea of always keeping your ego in check - and if you don't, your friends and family will take care of it for you! (Laughs.) So I said to myself: 'I don't want to believe that there's anything special about what I do. I just want to work.' Because for me, filmmaking is a profession - some people make shoes, others make films. It's a craft that you have to practice yourself. This way of thinking got to the point where, when someone approached me to adapt a book from the 'Millennium' series, I agreed immediately. And after I'd done it, it became clear to me that I shouldn't have done it, and that I'd have to think twice before embarking on a project that didn't suit me. It almost made me want to stop everything, because [on this film] I had been surrounded by too many people for whom films are not a religion. For them, it was just another film. After that, I was done, heartbroken, so to speak. Then came Covid - nobody was going to make films for a while, obviously. In order for me to decide to go back to directing, to make it really worthwhile, I knew that I had to be really passionate about a project, and that I had to believe in it. To tell the truth, I wasn't even interested in the idea of creating something new. I told everyone that the only thing that really got me going was ALIEN. That's how it happened, and I can see the connection with the fact that I've already directed licensed films, but... I just go with the flow. That's about it. Maybe I should inject more intellect into it but my decision-making is always emotional first.

A: Is there also a very special pleasure to have in seizing a world with its rules and codes - some to be respected, others to be subverted?

F: Oh yes, definitely! You know, filmmakers have always wanted to summon into their work the traces of past films they've loved. Not in the early days of cinema, because there weren't many films in existence. But from the moment cinema became this institution, the snake began to bite its own tail.Today, someone told me that ROMULUS looked like it had been inspired by an ALIEN video game that had been inspired by the films. We're in that cycle now. It's strange, but it's true. I had this discussion with Sam Raimi: he told me that he had wanted to adapt the comic 'The Phantom' but hadn't managed to get the rights, so he'd had to create his own thing, so he wrote DARKMAN .There are many such stories!

A: Starting with STAR WARS - Lucas wanted to adapt 'Flash Gordon'...

F: Exactly! There's a huge difference today: filmmakers still have the same ambition, except that the industry has it too. So that makes things easier. Even if I can assure you that just because you say 'I want to make ALIEN', they don't give you ALIEN.(laughs.) But this movement is historic. Earlier, I was talking about my influences with one of your colleagues. For me, the main influences are films you watch before you're 12 - they usually stay with you for life. In my case, it's easy because as a child I had three VHSs at home, which I watched over and over again. Everything, almost everything I know about cinema comes from these three films: MOBY DICK by JohnHuston, FRANKENSTEIN JUNIOR by Mel Brooks and SCARAMOUCHE by George Sidney. Your colleague asked me if I didn't want to make films like these, original films. I agreed. Then he left, and a few minutes later I went to see him to tell him that, in fact, these three films weren't original: SCARAMOUCHE is a remake of a 1923 film of the same name (by Rex Ingram, ed.), 'Moby Dick' had already been adapted before John Huston (notably by Lloyd Bacon in 1930, ed.).FRANKENSTEIN JUNIOR, it must have been the tenth or fifteenth FRANKENSTEIN, except that it was a comedy! You see? That's Hollywood. Having said that, it's true today I'm very keen to write an original script - and that's what my co-writer (Rodo Sayagues) and I are going to do, after ROMULUS.

A: The first ALIEN was, at its heart, a story of class struggle. In ROMULUS, you feature workers. Did you consciously desire to write a blue-collar story and inject the film with some kind of social commentary?

F: Yes. But I can't tell you exactly what the film's about, for fear of spoiling. You'll know when you see it in its entirety. Because imagine it's 1979 and I've directed the first ALIEN. You ask me about class struggle, and I tell you, indeed, the film is about that, and in particular about how people realize that corporations are being shitty to them and are only interested in their own profit. Back then, this was a radical idea. Today, it's not: we all know it! (Laughs.) If we'd discussed all this back in 1979, it would have spoiled the film's ending. It's the same here: I can't tell you what ROMULUS is about, but it's about the zeitgeist.That said, if I want to be an honest filmmaker, I have to understand why a film really works, and not get carried away by the intellectual dimension of the subject. Let me explain. With James Cameron, I once discussed TERMINATOR 2. I told him how it was a father-son story, with the T-800 assuming the position of surrogate father to John Connor, and so on. And he said: 'Yes but... it's actually a movie about guns'.I was astonished, but... think again. In the mind of the teenagers we were when we saw this film: the sound of the Beretta, absolutely unique, that never sounded like this; the image of Arnold swinging his shotgun around his finger to reload it; and then, it's an escalation, T2: gun against bigger gun, a weapon against a bigger weapon, and so on. It's a fetish! That's what makes it work. We all want to fixate on the intellectual part of films, and we neglect the crucial aspect that makes a film work, the one you can't take away. Take away the xenomorph and you no longer have ALIEN, you have something else. Recently, I showed MATRIX to my son because he was finally old enough to understand it. I presented it to him from an intellectual point of view, what it's about and so on. His reaction after watching it? ‘Yes, it's great. It's a kung fu movie!' He's right! That's what makes MATRIX so effective! It was the first time Americans and much of the rest of the world had seen a film movie that took up the Hong Kong way of doing action, with tethers. Except that you put it like that, it sounds silly. So we all try to raise the bar, to talk about it in a more sophisticated way. Of course, MATRIX is much more than that. But if you try to do MATRIX without the kung fu and the fighting, you're betraying its essence. So, to come back to your question: yes, there's this blue-collar dimension to ROMULUS but the part I didn't want to overlook was what made ALIEN in 1979 had such an impact on people - the shock, the violence, the dread. Of course, ROMULUS can’t be quite like that, because there are elements in it that are now too familiar for it to be. But if you're young, or if you've never seen an ALIEN, it could be. The aim is for it to generate an intense cinematic experience. I really wanted to be honest and not get too obsessed with the rest. Because otherwise, you know how it is: some films privilege intellect and sophistication over everything else.

A: I understand your argument, but it's also true that films interact with their time and that this creates a purpose - even an unconscious one. For For example, there has always been a symbolic sexual dimension in ALIEN - the hollowness, phallic shapes and so on. When you make ROMULUS in a post-MeToo, you can't ignore it...

F: Really, I try not to think about these resonances. All that could do is scare me and paralyze me! It would make me doubt every decision I make. I have absolutely no control over how people will interpret ROMULUS. All I can do is be faithful to the spirit of the original. But yes, as it happens the symbolism of H.R. Giger's work was very feminist. In the first ALIEN, the Face Hugger is a vagina that violates a man's face. These images

freed themselves from a lot of taboos. And I think the effect is the same today. It's because, in the best-case scenario, most people won't even see it. And besides, we shouldn't be able to explain all this too categorically. In ALIEN, it's all very subtle, in the end. But if you go back to Giger's art, it becomes obvious. Of course, they went to this guy to design these creatures! Giger was rejected for a large part of his career by the art community and the press because his work was deemed pornographic. But when you look at ALIEN, things aren't so apparent. Your subconscious sees it. It attacks you without you even knowing it. And that's why audiences enjoy it. I hope it will be the same in ROMULUS. People have to ask themselves: 'Is this what I think I'm seeing? But in the context of the scene, it can't be a distraction.

A: How do you approach directing?

F: I don't rehearse much because I want to keep things fresh for the shoot. Rehearsals can help, but on a film like ROMULUS, which isn't text-driven, you wouldn't get much out of it, I think. The actors can ask me questions about their characters, about anything that isn't verbalized in the script. I don't usually do storyboards either, except in very technical cases.

I like to arrive in the morning and walk around the set, so that I can walk around them. I start by choreographing the action. I give the actors a fair amount of freedom in terms of their reactions and movements, and we check technical factors - 'Don't go there, because I can't get the camera in that corner', etc. Then I shoot. This was the case on ROMULUS: most of the shots were decided on the spot. At first I thought it was a lazy method, but then I remembered that Spielberg, too, arrives in the morning and chooses what he's going to do. For me, it's a good way of being inspired by the elements at my disposal, rather than building a set that absolutely has to fit a storyboard we designed beforehand. There's no right or wrong method. Each to his own. I also like to be as realistic as possible, especially in terms of acting. I tend to hire actors who 'are' the characters. If I want a kid to be nervous, I won't hire an overly charismatic guy who will play at being nervous. My obsession is that the set should be a playground, but that all the elements should be there, in place, so that the characters can play. So everything has to be as real as possible. The creatures are there, the actors are close to their roles, and so on. It makes things easier, but above all, it makes the shooting experience more real. When tourists come to Paris, they take pictures of the Eiffel Tower to bring that feeling with them. That's my job as a director: I do everything I can to bring to the screeng. The creature's entrance, the actor's reaction. In the scenes you've seen, there's the moment when Isabela (Merced) sees the cocoon on the wall: she knew the scene from the script, but she had no idea what it would look like, how it would move, so her reaction to the image is visceral. For me, the tension and horror have to work on the set as if it were a play. If it's already working there, I know that the editing, music sound and colour grading will take the scene to an even higher level. I'm obsessed with this: the moment. That's also why I do very long shots. I don't shoot bit by bit. If an actor has to run a corridor, I put one camera at the beginning, another at the corner to cover, and another at the end, so that he does it all at once and ends up really out of breath. I like that because it transpires on the screen afterwards.

A: Cailee Spaeny says that in ROMULUS the acting tends towards ALIEN and the action towards ALIENS.

F: And it's true.

A: These are two films with very different tones. How did you work the balance?

F: I think we tried not to control things too much. Some of the best things happen when you combine two elements that have never been combined before. Like MATRIX, with its mix of kung fu and cyber conspiracy. It's the combination that creates the original. In college, one of my professors taught me the definition of modern:: it's when the new meets the classic. On ROMULUS, I didn't have to worry about the new. The new is everywhere, all the time. You can't escape it. The actors are young and new. They live in our time, and that influences the way they move, behave and so on. The optics we use are new light isn't the same today as it used to be, and so on. Even though we try to be as close as possible to the original film, the technology doesn't do the same as it did back then. But we've also pushed in the other direction so that certain parts seem to come from another period. For example, with language, when the characters swear. We avoided swearing that was too modern, to make it seem more 'classic'. - you'll see, the way they say 'you son of a bitch!’ they say it like that! (Laughs.) We also embraced the best of classical techniques with lots of animatronics. Hopefully, all this will make the film modern, never too old-fashioned, never too new, never too 'now'.

A: At the time of DON'T BREATHE, you told us that writing horror was a catharsis, a way of projecting your fears into a story. With ALIEN, what fear are you exorcising - especially if it was the only project you really wanted to do?

F: I don't know what it is! It's almost frightening, actually. You know, my films are really honest. They really are. Especially since I write them. Even if some of them are set in pre-existing worlds, our characters are always new - except in MILLENIUM and maybe that's why I didn't enjoy the experience. So each time, we created characters and stories within a framework that already existed, and that allowed us to make them our own. It's fascinating and strange: I'm 46, I look back at my work and wonder what could have happened to me to write and direct films like this! Why do I gravitate towards these subjects? Quite clearly, everything in my films scares me. I couldn't create a moment of horror that didn't frighten me. Just now, when we were showing you the extracts, I was still in a panic! You see the cocoon that looks like a vagina, and all of a sudden, a thorn sticks out? It terrifies me. This kind of imagery inevitably comes from what I find disturbing. Why do you think that is? I've no idea. Ask my parents about my childhood! (Laughs.) I don't even want to know. Firstly, because I want to continue to feel this fear. Fear is exciting. It teaches you a lot about yourself. As soon as you know where it comes from, it's no longer scary and becomes... vulgar. Getting answers obsesses us all. But as has often been said, art is all about questions.

CAILEE SPEANY INTERVIEW

She's only 25, but you feel as if you've always known her - the lot of great actresses. It has to be said that 2024 was her year, with breathtaking performances in PRISCILLA and CIVIL WAR. Before starring opposite Daniel Craig in Rian Johnson's third KNIVES OUT, Cailee Spaeny is set to further refine her status with ALIEN: ROMULUS. Here’s an interview with an exciting actress who's never been in the same place twice.

BY AURÉLIEN ALLIN

A: In PRISCILLA and CIVIL WAR, your characters were partly observers. In ALIEN: ROMULUS, your character can't be, she has to act. Is this a coincidence, or did you seek this shift?

Cailee Spaeny: The only thing I'm really aware of when I take on a role is my desire to be a thousand miles away from the previous film. In terms of tone, going from CIVIL WAR to PRISCILLA (editor’s note: released later, CIVIL WAR was shot before PRISCILLA), then going from PRISCILLA to ALIEN was really embracing opposite worlds, and it required [of me] something totally different. In my work, you have to put a lot of thought into the character's arc. On ALIEN, at the start, I kept asking myself, ‘What’s her arc?’ Then I realized that you get an arc if you throw a person into a terrifying situation, where they're being stalked. That's the bow! And then, as you say, the character throws himself into the action. It's a real gift because you don't don't have to ask yourself: 'Where are the subtle changes [in the character] over the years? (Laughs.)

A: Your performances in CIVIL WAR and PRISCILLA were very dense and subtle. Is this possible on ALIEN, where you project a character into the action? And above all, is it necessary?

C: It's still necessary, yes. You still have to anchor the performance in something more action and horror, otherwise who cares? If you don't care about the characters, you'll just have one death after another with nothing at stake. That's what's so fascinating about the very first ALIEN: when we're introduced to the characters after they've woken up, you've got Harry Dean Stanton, Yaphet Kotto, Sigourney Weaver and so on. These are all actors. There's not much to establish their characters, but the actors are all so natural and their relationships so convincing... They don't talk about their families, they don't talk about their families, the script doesn't give them any backstory, but the bond between them is very strong. You feel an instant connection with them and for me, that's what makes ALIEN so terrifying. On the set, Fede (Alvarez) was constantly reminding us that we had to forget about the horror film and ask ourselves what our performances would be if this were an independent film. At times, the aim was to subvert the typical action-movie tone, and at other times to embrace it. There's a shot, for example, where I emerge from an elevator armed with a machine gun - behind the camera were two technicians with blowers: a pure ALIENS moment! We were constantly moving from one tone to another, and we had to find the right balance.

A: How do you go about building a character? Do you start with the character's inside or from the outside?

C: It helps to have something physical to hold onto. On CIVIL WAR, it was the camera. On ALIEN, I trained myself by telling myself that Rain was from a mining colony. So she's very physical and used to hard jobs. That immediately set the tone for the character. Then I thought about my own roots: I come from the Midwest of the United States, from a blue-collar background and a line of farmers. So I thought about who these people are, what they look like, what their temperament is, and so on. That was the starting point.

A: But do you have a set method for building a character?

C: No, not really. It's all a big mishmash: I'll read a book, watch tons of films, write the character's diary, train physically, look for a new way to learn my lines... and see what all that brings me or doesn't bring me.I throw it all into the blender, look at what's left and then try to forget it all and see what comes out on the first day of shooting. In PRISCILLA, many things came through your immobility: her rage, her joys, here rage, her joys, her sorrows, her strength.

A: Was it a physical performance for you?

C: Yes, in an extremely subtle way. Everything depended on tiny things. What is the impact of a blink of an eyelid, at that precise moment, in close-up? A very slight tilt of the head? For Sofia (Coppola, ed.), the devil is in the details - on the hands, on the feet; the emotional nuance when I put on my false eyelashes, etc). I had a blast doing all that. I came to know my face perfectly. (Laughs.) I never look at my shots on the monitor, that would be over-reflect, but on PRISCILLA I had to be hyper-aware of my every move because they all made a lot of sense.

A: Did it help you with ALIEN and this more overtly physical role?

C: I think it'll come in handy for all my roles. But ALIEN was very different. Particularly in the third act: it was very physical, and everything was based on moving a lot, you had to use your whole body to convey the shock, the horror, the survival instinct and so on. You know, I didn't study acting. I didn't receive any training. My school is filming. I learn different techniques on the job. It's a lot of fun, but it's also terrifying because if it doesn't work, it is immortalized on the screen for all eternity. (Laughs.)

A: Do you feel that it's harder to impose yourself and your character on films like PACIFIC RIM: UPRISING and ALIEN, because you're competing with a show, creatures and effects?

C: No, it just requires something else. I'd like to be able to tell you that in every film, as soon as the camera starts rolling, the character takes over, you become someone else and enter this higher state. I assure you, it's rare. At least for me. Because you've got a guy next door who's manipulating a puppet of some creature and making a little noise, and you're trying to figure out how to stay terrified during the six months it's going to

take to shoot... So most of the time, I use tricks of the trade. On PRISCILLA, we only had 30 days to shoot - that required something else. I can't tell you any better: it's different. I love all films, all genres, all styles of acting. ALIEN and ALIENS were very distinct in terms of tone, but also in terms of acting - because one was made in the 70s, the other in the 80s. And in my eyes, one is no better than the other. Both require technique and precise skills, particularly in understanding the tone of the film and convey it in the best possible way.

A: According to Fede Alvarez, ROMULUS is precisely halfway between ALIEN and ALIENS. Where did you see the balance in the game?

C: I think that on ROMULUS, the acting tends towards ALIEN, while the action tends towards ALIENS. In any case, we were constantly discussing it, testing things out, trying to find the balance. I trusted Fede completely because he knows this franchise like the back of his hand.

A: Without going into the cliché of "the new Ripley", did you have to reflect on this legacy? this heritage? Or did you decide to ignore it?

C: I don't know if it's a good thing or a bad thing, but I can't remember ever having struggling with the subject. I knew how I wanted to play the role. I also knew that that I loved what Sigourney had done - I swooned over her acting and her screen presence. Maybe, through the study of her performance, something happened... But Sigourney is truly singular. So there couldn't have been any real debate in my head. It wasn't even a challenge, because I wouldn't have been able to win that battle!

A: I read that on CIVIL WAR, you refused to wear your earplugs in the action scenes because you wanted to "feel things".

C: (She grimaces)

A: I don't know if that's true...

C: It's true, yes. And it wasn't very clever of me, I know. But be tolerant, I'm in my twenties!

A: On a film like ALIEN, with the multitude of angles to be covered, effects etc., is it possible to "feel" things? Or is there a distancing?